Summary of Research Findings

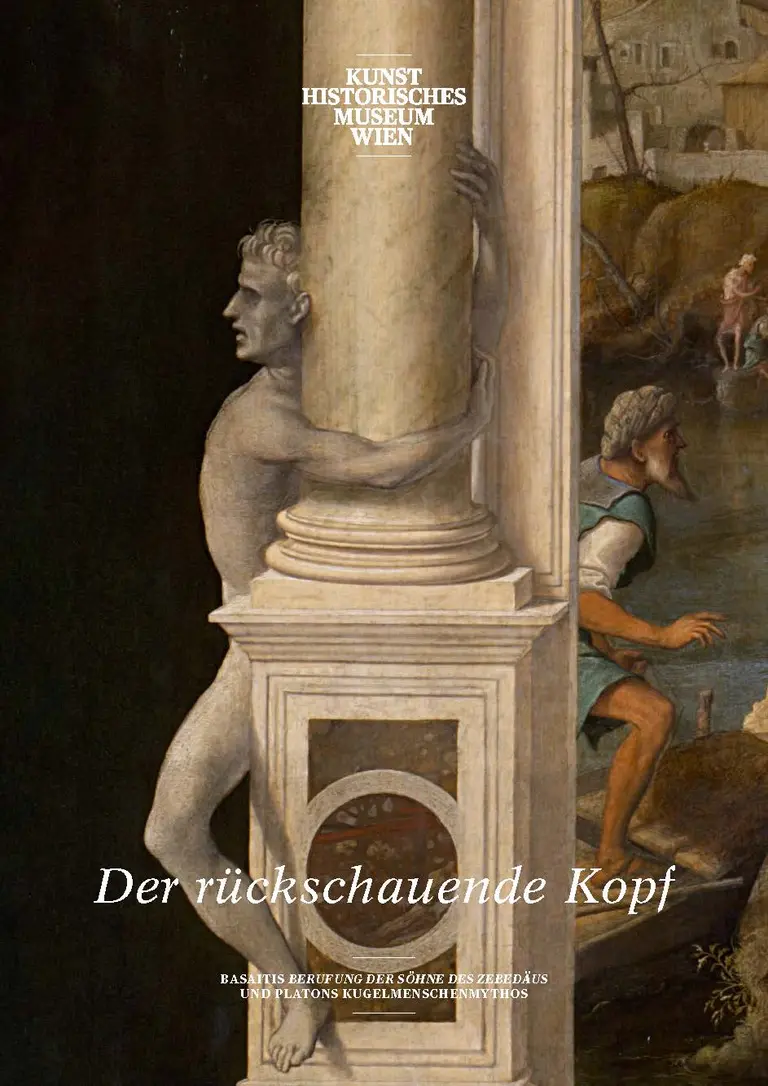

The identification of the hitherto mysterious grisaille men on the painted architectural frame enclosing a depiction of the calling of the disciples that is in itself true to the gospel account makes it possible to put a completely new interpretation on the painting, which is now more than five hundred years old. The left-hand grisaille man with his apparently back-to-front head is a reference to Aristophanes’ myth as found in Plato’s Symposium, according to which the original humans were dual beings with two faces looking Janus-like in opposite directions, spherical in shape with four arms and four legs; as a punishment for their rebelliousness, Zeus cut them in two, making two beings who thenceforth desperately desired to reunite with their original ‘other half’. According to the myth, following separation there was an intermediate phase in which the individuals looked backwards, before receiving their final form with their face and genitals turned to the side of the stomach, that is, their new front.

In the essay, through step-by-step argumentation based on antique, biblical, and humanist sources (all quoted in both the original language and English), the nature of the left-hand grisaille man becomes clear: he has only just been separated from his partner and thus still has his backward-looking face. In the case of the right-hand figure, by contrast, whose anatomy seems to be entirely normal, the operation making him into a modern man has been successfully completed.

This identification leads to the interpretation. In Aristophanes’ myth, the cutting into two of the spherical dual beings with the resultant desire for the lost partner is presented as the origin of love and sexual desire. In the case of two separated male halves this desire is homosexual, which Plato claims is nobler and more manly than heterosexual desire. Given that grisailles were customarily incorporated into otherwise polychrome paintings in order to add a further and deeper level of meaning to the painting’s main motif, the next step is to focus upon the inner thematic link between the myth of the calling of the disciples and Aristophanes’ myth, which clearly lies in the theme of loving attraction between the protagonists. In both cases, the subject is that of the ending of separation and of coming together. In the centre of the painting, Jesus is seen choosing his disciples and calling them to join his closest circle of companions, following which he lived together with them – John being of special interest in this respect because in St John’s Gospel he is consistently referred to as ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved’. Similarly, on the architectural frame the left-hand figure is calling for his beloved partner, while the right-hand one is discovering and clearly relishing his new physicality, with which, according to Plato, he will be able to satisfy his desire temporarily by sexual means.

Why did the inventor of the picture choose to refer to Plato’s dual beings in order to deepen the understanding of the calling of the disciples? Both myths celebrate attraction between men, though sexual love only becomes an overt factor in the Symposium and not in the gospels. It would be possible to interpret the combination of depictions in Basaiti’s painting as presenting the thesis (encoded on account of its scandalous nature) that Jesus and John entered into a homoerotic partnership. However, this would be to miss the point, because at the beginning of the sixteenth century Plato’s Symposium was read in connection with the famous commentary published in 1484 by the Florentine scholar Marsilio Ficino, who saw Plato’s myth as a religious drama in which the two former male halves were not homosexual men as in the Symposium but, true to Ficino’s Christian world view, two lights, one divine and attractive, the other human and attracted, through whose unification the human soul, separated from the divine, is restored to wholeness. While this interpretation differs greatly from Plato’s myth, in which the two mutually attracted halves are equal members of the human world, it corresponds very aptly to the unequal attraction between Jesus, who according to the Christian myth was divinely conceived, and the beloved and completely human disciple John.

The connection forged between the two myths in Basaiti’s painting is thus to be understood in the light of Ficino’s idiosyncratic interpretation of Plato (which does not do justice to the philosopher’s intended meaning), because it is only in the special case of the attraction between Jesus and John that Ficino’s personal interpretation is tenable. Thus, we may ask, was the painting perhaps conceived as a posthumous defence of a great scholar? On the other hand, the reciprocity of love between Jesus the Son of God and individual human beings is the subject of the saying of Jesus as given in St John’s Gospel (14:21): ‘He who has my commandments and keeps them, he it is who loves me; and he who loves me will be loved by my Father, and I will love him and manifest myself to him.’

Even though this literature-based explanation of the unique depiction is undeniably plausible, there remains the at that time highly explosive – and potentially fatal – theme of homosexuality, which is a central element in Aristophanes’ myth and would have immediately occurred to any humanist who had read the original text and associated the grisaille men with it.

The present essay investigates the essential factors from the cultural context of Venice at the beginning of the sixteenth century that contribute to our understanding of the painting: the significance of grisailles, intolerance of homosexuality, the humanist reception of Plato, academic syncretism, and four literary interpretations of Aristophanes’ myth that would have been accessible to any interested party at the time, all of which go out of their way to avoid the subject of homosexuality.

In the present state of research into Basaiti’s life and cultural resources, it cannot be said for certain whether he himself had the idea for his painting. If the idea derived from the art patron who commissioned the work, then he will presumably have been a humanist scholar, perhaps homosexual, who intended to have his private devotional image enriched with a precious and high-minded manifesto of Neoplatonic erudition and acceptance of homosexual love, a liberal outlook that it would have been dangerous to express verbally at a time when homosexuality was considered an unnatural vice and prosecuted under the law. On the other hand, couched in the form of a pictorial element that called for (but did not specifically require) erudite interpretation, the non‑verbal testimony has been able to come down through the centuries undetected.